David on Technical Topics – Cognac Grape Varieties

Most people regard the Ugni Blanc as the cognac grape variety but there are in fact 8 different varieties allowed in the production of cognac. The Ugni Blanc is also known as the St Emillion des Charente, but the Colombard, Folle Blanche, Jurançon, Blanc Ramé, Bouilleaux, Belzac Blanc and Chalosse grapes are also permitted. More than 95% of all cognacs are made from the Ugni Blanc which was originally an Italian variety called Trebbiano Toscano, from the foothills of the Emilia Romagna near Piacenza. It is regarded by many as being so widely used that it probably produces more wine than any other variety in the world albeit under a number of different names. Its popularity is contrasted by its qualities which can be summed up as pale lemon, little nose, notably high acid, medium alcohol and body and short. It produces a quite unremarkable and characterless wine but it has two important qualities for making cognac. Firstly it maintains its acidity right up to even quite late harvests and secondly it produces huge yields. These qualities produce a relatively neutral base for distillation.

The Ugni Blanc vines are planted about 2.8 metres apart and usually stand around 1-1.5 metres tall. They are cultivated along wires in rows to make it easier for machines to spray and harvest them. The yield can vary according to the weather but most vineyards produce more than 30,000 litres of wine per annum which will make at least 3000 bottles of cognac. The wine produced from these grapes, apart from being fairly neutral is only around 8 – 10 % abv making it very suitable for the distillation process.

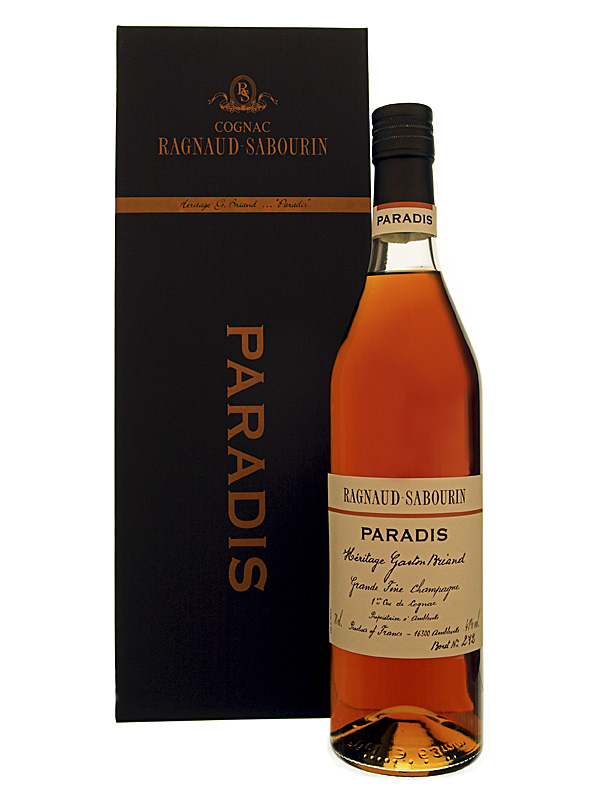

More adventurous growers will combine the Ugni Blanc with Folle Blanche and Colombard grapes. The latter can provide some delightful peachy aromas in the cognac. Our award winning Hermitage 10 Year Old is an excellent example of this grape combination as it has aromas of dried peach and apricot with flavours of vanilla, toffee and a little citrus. The firm of Ragnaud Sabourin, in Grande Champagne, actually uses all eight varieties in its delightful, but expensive, 1903 ‘Cognac Paradis’.

Our Hermitage 10 Year Old Cognac is on offer this month so now is the perfect time to taste it and see if you can tell that it has been made using different cognac grape varieties.

To read more Technical Topics, go to the Brandy Education page of our Blog.