Single Cask Cognac – Whyever Not?

Single Cask is a term well known in the whisky industry, it certainly gives a product increased status and price but why is that? The phrase Single Cask suggests a unique glimpse into a particular set of circumstances that has given rise to a one-off personality. The whisky may be from a certain year where the distillery was using a particular mashing regime, yeast strain or set of stills. It may have been stored in a warehouse that is known to provide certain conditions. The barrel itself is unique as no two trees are identical and coopers’ techniques differ, so the flavours that develop will be only found in that cask. Every distillery has its official range of bottlings which are created to please as many people as possible, but a Single Cask captures the stage before the identity is lost in the blend. For distillery fans, this takes their experience a step further. Rarity imparts value and so a Single Cask will be highly sought after.

Single Cask is a term well known in the whisky industry, it certainly gives a product increased status and price but why is that? The phrase Single Cask suggests a unique glimpse into a particular set of circumstances that has given rise to a one-off personality. The whisky may be from a certain year where the distillery was using a particular mashing regime, yeast strain or set of stills. It may have been stored in a warehouse that is known to provide certain conditions. The barrel itself is unique as no two trees are identical and coopers’ techniques differ, so the flavours that develop will be only found in that cask. Every distillery has its official range of bottlings which are created to please as many people as possible, but a Single Cask captures the stage before the identity is lost in the blend. For distillery fans, this takes their experience a step further. Rarity imparts value and so a Single Cask will be highly sought after.

Many of these special characteristics can also be found in cognac production. Every year the very best cognacs are selected for long-term ageing, rather than joining the thousands of others destined to be blended. The cellarmasters’ skills are paramount in bringing these chosen nectars to optimum maturity and many variations to the ageing process maybe employed. So why are these cognac vintages or age statements not designated as Single Cask? Perhaps the answer lies in the finer detail.

Amazingly, an industry-wide definition of Single Cask does not exist, but The Scottish Whisky Association (SWA) is clear on the rules that it enforces. They feel that to be classed as Single Cask, the spirit must remain in the same barrel from the moment the spirit is filled until the moment it is bottled, without any revatting or finishing. Therefore “a sherry finished single cask whisky” is not acceptable but a “single cask whisky finished in a sherry butt” is. It is accepted however, that all whiskies will move from one barrel to another in the early stages of maturation, it is what happens next that is important.

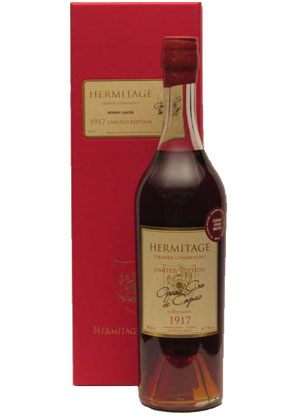

The process of moving from new to old wood in the initial stage also applies to cognac so, when a vintage is kept in the same old oak barrel throughout its maturation, it will be Single Cask. A problem arises though when there are multiple barrels of the same vintage which may be mixed for bottling. Unlike in the whisky industry, barrel numbering is not common. Cognacs can also be moved to different barrels during the ageing process. The cellarmaster seeks to guide the spirit’s maturation path by using newer and older oak barrels at different stages. This can really benefit the final quality and flavour of the cognac so is deemed to be more important than any benefits derived from being Single Cask. The rules of cognac production are strict; it may not be put into barrels that have held other types of spirit, but it may be put into previously used cognac barrels. The BNIC’s definition of Single Cask is a cognac that has always been stored in the same barrel so, the phrase could indeed be used to describe a particular barrel of cognac, but not as often as you might expect.

There are all manner of theories, assumptions and legends relating to the actual birth of

There are all manner of theories, assumptions and legends relating to the actual birth of  We place much emphasis on the ageing of

We place much emphasis on the ageing of  The concept of barrel ageing is said to have been conceived by wine merchants when shipping their wines from the harbour at La Rochelle. The weak and commonly sweet wines that were shipped along the Charente from Cognac often became rancid. The wine merchants therefore reduced their volume by distillation, before shipping abroad in oak barrels. After their arrival in foreign ports it was noticed that the clear distillates within had coloured and gained in flavour.

The concept of barrel ageing is said to have been conceived by wine merchants when shipping their wines from the harbour at La Rochelle. The weak and commonly sweet wines that were shipped along the Charente from Cognac often became rancid. The wine merchants therefore reduced their volume by distillation, before shipping abroad in oak barrels. After their arrival in foreign ports it was noticed that the clear distillates within had coloured and gained in flavour.

We have often talked about distillation on the Lees but rarely described why we do it or indeed what ‘the lees’ are.

We have often talked about distillation on the Lees but rarely described why we do it or indeed what ‘the lees’ are.