Category: The History of Cognac

Hermitage 1914 Cognac – The Ladies Vintage

We were fascinated to read an interview with Bénédicte Hardy in ‘Frenchly’. Bénédicte is the fifth generation to be involved with the House of Hardy cognacs, although much of her time has been spent working in the US. Entitled ‘Cognac’s returnRead more

Why Is Cognac So Popular In China?

While Baijiu is the undisputed national spirit of China, cognac is the drink of choice for the country’s elite imbiber. This tradition started about 200 years ago when Shanghai became a treaty port and some of the first companies toRead more

National Cognac Day – 4th June

Did you know it was National Cognac Day last month? A relatively new addition to the annual calendar and originating in the United States of America, it is celebrated on the 4th of June. As with all popular, American activitiesRead more

The Australian Connection with Prunier

During the years after the gold rush in the 1850s, brandy became the most popular spirit in Australia. French companies were quick to seize the opportunity and in 1870 Prunier opened a branch there. A loyal following for the brandRead more

The Price of Cognac History

M Restaurant has announced that it is to sell its bottle of 1894 cognac for over £6000 for a 25ml shot – that’s the price of cognac history. The bottle is reputedly the first blend ever produced by Jean Fillioux,Read more

Why is the French ‘Paradis’ so special?

Not every cognac house has a Paradis – a designated area in the innermost recess of their cellar – but those that exist are steeped in history. Back in the early eighties, having discovered a cognac which I really liked,Read more

Why are rose bushes planted in vineyards?

On a recent trip to the Charente I took this picture of a rose bush at the end of a row of cognac vines. This placement of rose bushes has created considerable interest from our followers. I therefore thoughtRead more

UK Alcohol Duty and its Enforcement

During the 18th Century smuggling in Cornwall was a way of life. It is said that at its peak, more than 500,000 gallons of French brandy was smuggled in per year. This equates to more than two million bottles. WholeRead more

Cognac Crus

Cognac is produced in the delimited region of France known as the Charente and Charente Maritime which borders on the Atlantic Ocean. To the west the region borders on the Gironde estuary and includes the islands of Ré and OléronRead more

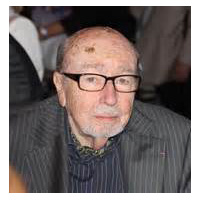

Max Cointreau Dies

One of the most highly regarded names in the cognac industry, Max Cointreau, died on 19 October at his home in Gensac la Pallue, near Cognac aged 94. Max was joint managing director of Frapin, in the heart of GrandeRead more