There are all manner of cognac classifications found on bottle labels, but what do they actually mean? Most of the generic terms below describe cognacs made by blending hundreds, or even thousands, of cognacs together to produce a vast quantity of a homogenous product for sale on supermarket shelves. As demand increases younger and younger cognacs are used in these blends so sugar syrup and caramel colouring are added to obscure the fieriness on the tongue and lack of appealing colour.

There are all manner of cognac classifications found on bottle labels, but what do they actually mean? Most of the generic terms below describe cognacs made by blending hundreds, or even thousands, of cognacs together to produce a vast quantity of a homogenous product for sale on supermarket shelves. As demand increases younger and younger cognacs are used in these blends so sugar syrup and caramel colouring are added to obscure the fieriness on the tongue and lack of appealing colour.

VS stands for Very Special. Also known as *** (3-star) or Premium, the youngest eau-de-vie in the blend must be at least 2 years old. Many of these younger cognacs are purchased by the ‘Big Four’ companies in order to meet their ever-growing demand.

VSOP stands for Very Superior Old Pale. The youngest eau-de-vie in the blend must be at least 4 years old. The colour of cognac deepens the longer it stays in contact with the wooden barrel. Although described as ‘Pale’ these young cognacs can also have caramel added which provides a red glow.

Napoleon. Named after the very famous Frenchman, Napoleon Boneparte, the youngest eau-de-vie in the blend must be at least 6 years old. Up until April 2018, this was also the age of XO.

XO stands for Extra Old and must be aged for a minimum of 10 years. Although not official terms, Extra and Hors d’Age are often used to describe cognac of XO quality and age. Some small producers sell XO that maybe up to 20 years old but, it is unlikely that this will be specified on the label.

XXO is a new classification that stands for Extra, Extra Old and the youngest eaux-de-vie in any blend must have been aged for a minimum of 14 years.

Other terms such as Reserve, Très Vieille and Heritage are often used to describe blends that are much older than XXO although none are official nomenclature. They could be 15 or 50 years old.

So you can see that it is very difficult to decipher exactly what is in your bottle of cognac with a generic label as only minimum ages are specified and they are highly blended. Sometimes Single Estate is used to describe a cognac where all the eau de vie used has come from the same estate. In this case, far fewer cognacs will be used to make the blend so the flavour should be more individual.

Cognacs with Age Statements (eg 30 Year Old) are more precise as they list the youngest eau de vie used and may also comprise a blend of just one or two cognacs or indeed be Single Cask (unblended). Vintage Cognacs also give you specific information. The year on the label describes the year the grapes were harvested. The cognac will be aged to perfection before being taken out of the wood and placed in glass when it will no longer mature. Most vintage cognacs will tell you when the cognac was bottled and therefore, for how long it was aged. This is the category that has the most information available to you, the customer. They are expensive to produce as the casks are strictly controlled throughout the decades of ageing. However, you can be sure that you are drinking cognac that has been matured to its optimum level, is unblended and has an unbelievable variation of aromas and flavours. We call this complexity.

Cognacs with Age Statements (eg 30 Year Old) are more precise as they list the youngest eau de vie used and may also comprise a blend of just one or two cognacs or indeed be Single Cask (unblended). Vintage Cognacs also give you specific information. The year on the label describes the year the grapes were harvested. The cognac will be aged to perfection before being taken out of the wood and placed in glass when it will no longer mature. Most vintage cognacs will tell you when the cognac was bottled and therefore, for how long it was aged. This is the category that has the most information available to you, the customer. They are expensive to produce as the casks are strictly controlled throughout the decades of ageing. However, you can be sure that you are drinking cognac that has been matured to its optimum level, is unblended and has an unbelievable variation of aromas and flavours. We call this complexity.

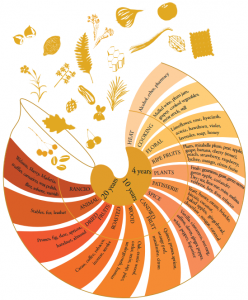

For many years we have been using a very impressive aroma wheel, set up by the BNIC, to help us describe the different aromas detected in cognac. I suppose it was inevitable that the Armagnaҫais would come up with something similar. So, instead of a wheel, armagnac aromas have been described in a round seashell with a collection of fruit, herbs, nuts and flowers floating mysteriously from the shell aperture. There are a number of other surprises too since the shell is split into three sections. The inner section denotes a range of ages, 4, 10 and 20 years, and linked to each a number of general types of aroma such as heat, cooking, plants, woods, animal and rancio. The outer section lists detailed aromas associated with each. Some are familiar smells such as dates, cedar, cinnamon and plums but those of ether, pharmacy, soap, resin, sap, stables and varnish are much less appealing. I’m not sure how much I would be tempted to taste an armagnac exhibiting any of these aromas!

For many years we have been using a very impressive aroma wheel, set up by the BNIC, to help us describe the different aromas detected in cognac. I suppose it was inevitable that the Armagnaҫais would come up with something similar. So, instead of a wheel, armagnac aromas have been described in a round seashell with a collection of fruit, herbs, nuts and flowers floating mysteriously from the shell aperture. There are a number of other surprises too since the shell is split into three sections. The inner section denotes a range of ages, 4, 10 and 20 years, and linked to each a number of general types of aroma such as heat, cooking, plants, woods, animal and rancio. The outer section lists detailed aromas associated with each. Some are familiar smells such as dates, cedar, cinnamon and plums but those of ether, pharmacy, soap, resin, sap, stables and varnish are much less appealing. I’m not sure how much I would be tempted to taste an armagnac exhibiting any of these aromas!

There are all manner of cognac classifications found on bottle labels, but what do they actually mean? Most of the generic terms below describe cognacs made by blending hundreds, or even thousands, of cognacs together to produce a vast quantity of a homogenous product for sale on supermarket shelves. As demand increases younger and younger cognacs are used in these blends so sugar syrup and caramel colouring are added to obscure the fieriness on the tongue and lack of appealing colour.

There are all manner of cognac classifications found on bottle labels, but what do they actually mean? Most of the generic terms below describe cognacs made by blending hundreds, or even thousands, of cognacs together to produce a vast quantity of a homogenous product for sale on supermarket shelves. As demand increases younger and younger cognacs are used in these blends so sugar syrup and caramel colouring are added to obscure the fieriness on the tongue and lack of appealing colour. Cognacs with

Cognacs with

Recent sales of some rare vintages have only served to highlight the value of old vintage cognacs. Prices of more than £200k a bottle were achieved on two occasions and we have seen other mouth-watering prices being paid. But not only have the prices of

Recent sales of some rare vintages have only served to highlight the value of old vintage cognacs. Prices of more than £200k a bottle were achieved on two occasions and we have seen other mouth-watering prices being paid. But not only have the prices of  In many ways, the concept of a

In many ways, the concept of a  The term “brandy” refers to a spirit distilled from a fruit. This includes

The term “brandy” refers to a spirit distilled from a fruit. This includes  Well, we all understand that cognac is aged in oak casks. Initially it is put into new ones and then, after about 6 – 12 months, it is transferred into old ones. When the casks are new, they are toasted to destroy the harmful tannins in the wood. At this stage, only the good tannins are available in the wood allowing the cognacs to develop their colour and flavour. Many cognac producers will ask for a specific grade of barrel toasting to suit the desired quality of the finished cognac. Repeated use of the new barrels means that over time, they will become old barrels and so used for long term cognac storage. However, as the tannins in the wood are used up, the inside surface of the barrel will gradually degrade leaving a cloudiness in the cognac.

Well, we all understand that cognac is aged in oak casks. Initially it is put into new ones and then, after about 6 – 12 months, it is transferred into old ones. When the casks are new, they are toasted to destroy the harmful tannins in the wood. At this stage, only the good tannins are available in the wood allowing the cognacs to develop their colour and flavour. Many cognac producers will ask for a specific grade of barrel toasting to suit the desired quality of the finished cognac. Repeated use of the new barrels means that over time, they will become old barrels and so used for long term cognac storage. However, as the tannins in the wood are used up, the inside surface of the barrel will gradually degrade leaving a cloudiness in the cognac. There are all manner of theories, assumptions and legends relating to the actual birth of

There are all manner of theories, assumptions and legends relating to the actual birth of  We place much emphasis on the ageing of

We place much emphasis on the ageing of  The concept of barrel ageing is said to have been conceived by wine merchants when shipping their wines from the harbour at La Rochelle. The weak and commonly sweet wines that were shipped along the Charente from Cognac often became rancid. The wine merchants therefore reduced their volume by distillation, before shipping abroad in oak barrels. After their arrival in foreign ports it was noticed that the clear distillates within had coloured and gained in flavour.

The concept of barrel ageing is said to have been conceived by wine merchants when shipping their wines from the harbour at La Rochelle. The weak and commonly sweet wines that were shipped along the Charente from Cognac often became rancid. The wine merchants therefore reduced their volume by distillation, before shipping abroad in oak barrels. After their arrival in foreign ports it was noticed that the clear distillates within had coloured and gained in flavour. Brandy has long been used for medicinal purposes, both internally and externally. We read that it was often used in Nelson’s Navy as an antiseptic, sometimes as an anaesthetic and even before then, as a digestif to sooth the effects of eating too much or too rich food.

Brandy has long been used for medicinal purposes, both internally and externally. We read that it was often used in Nelson’s Navy as an antiseptic, sometimes as an anaesthetic and even before then, as a digestif to sooth the effects of eating too much or too rich food.